Native American Skies: Perceiving Spring

- Mar 20, 2014

- 4 min read

Twice a year, a day comes along where the length of daylight equals the length of darkness. Today we call that day the “equinox”. We recognize the vernal equinox as the first day of spring and the autumnal equinox as the first day of fall. These two days have always been important indicators for man since even ancient times.

Before Europeans came to America, Native Americans did not have bankers, insurance agents, or real estate agents so where did they get their calendars? How did they know when spring or fall arrived? They had someone more important to them than our bankers or agents are to us, they had astronomers.

Due west of my house are two massive mountains, Crestone Peak and Crestone Needles. Both tower above the valley at an altitude of over 14,000 feet. They form an “M” shape and on the equinox, the sun sets right in the “V” between the peaks. Even without my complimentary calendars, I know when spring arrives just by observing the sunset. Ancient astronomers used the same technique to perceive the seasons and know when to schedule their planting, harvesting, and observe their important ceremonies.

In the arid canyons of Chaco Wash in northeast New Mexico, the capital city of the great Anasazi civilization once thrived. One thousand years ago, as many as two-hundred gaily dressed men and women sat on stone benches that lined the circular walls of a great kiva. Festive dancers waited in side rooms as prestigious priests stood in the center watching a small, square niche built into the west wall. As the sun rose, its rays shown through a small window in the east wall of the kiva and the square light slowly descended the west wall until it lit up the niche. The priests announced the first day of spring as the people cheered and the dancers flowed onto the floor to begin the celebration.

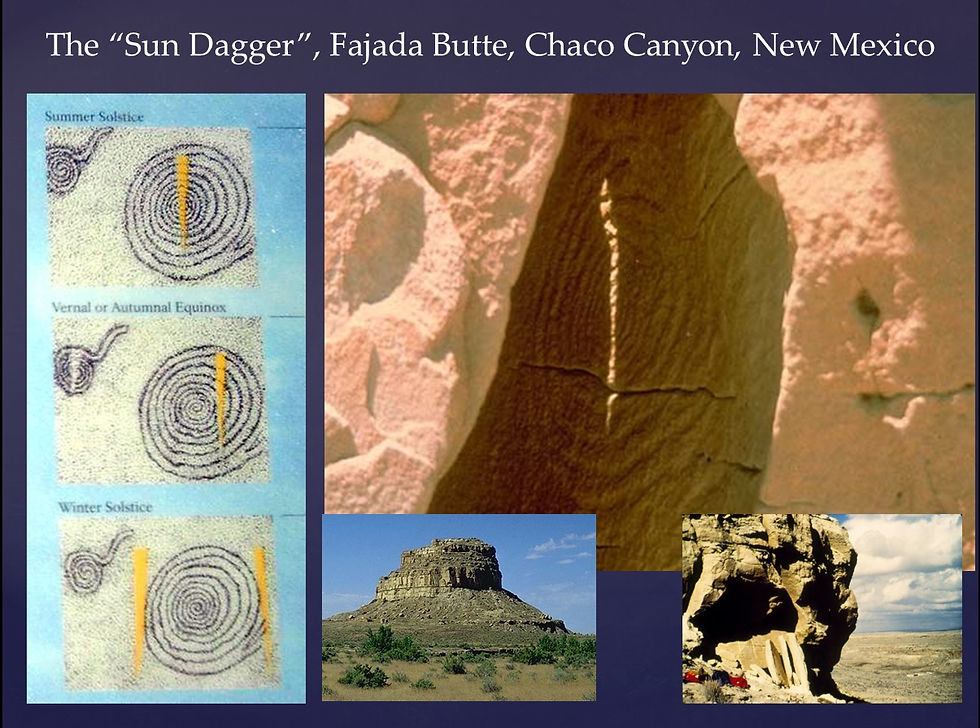

Not far away, sitting atop a 700-foot butte, crouched and shivering under colorful blankets, the village astronomer(s) watched and waited for the sun to climb above three stone slabs leaning precariously against the cliff face. Behind the slabs, they had chiseled a large spiral and a smaller one carefully expanding them over time based on their observations. Around noon, a sliver of light began to form and slowly grew forming a long dagger of light bisecting the third line encircling the larger spiral. Then a smaller dagger formed across the center of the smaller spiral. They rejoiced. These daggers of enlightenment confirmed that it was, indeed, the first day of spring!

Over one thousand miles away, the massive capital city of the Mississipians (mound builders) spread out across the Mississippi river. The high chief and priest stood atop to lower tier of an enormous two-tiered mound. They faced the east and waited for the morning sun. To the west, 48 equally spaced, tall cedar posts formed a 476-foot circle with one cedar post in the center. The primary astronomer stood with his back to the center post and sighted across a post due east. He knew that that day the sun would rise in alignment with that post and the front edge of the chief’s mound denoting the arrival of spring.

To the north and west, nomadic hunters and their families have congregated around a large circle of stones with a pile of stones forming a cairn in the center and smaller stones radiating out like spokes to connect with the outer circle. The man-made formation originally built three-thousand years earlier by their ancestors looks like a giant wagon-wheel laying on its side. The designated astronomer, probably the head medicine man, walks to the center and stands on the center cairn and sites along one of the “spokes” across a cairn built along the outer circle. The sun will rise in alignment with this spoke to announce the spring equinox. Soon they will be able to journey further north to hunt.

For the indigenous people of the Americas, the vernal equinox meant much more than a time to replace batteries in their smoke detectors. It reaffirmed the order of things. It was a time to plant new crops or to move north to hunt buffalo, elk, or caribou. It meant the end of the long, cold winter for the tribes of North America or the end of summer for the tribes of South America.

Their elegant calendars reflected the ingenuity, creativity, and devotion of the Native American and his pursuit of harmony and balance with nature in his quest for the good life. Today we can only study and admire their great achievements through the science of archaeoastronomy, the study of how the ancients understood the phenomena of the sky and the role it played in their culture.

Tonight when you sit down to watch your big flat screen TV, take a moment to imagine the ancients sitting down to watch their 3D, HD, big screen–the sky.

— Courtney Miller

![Kawoni [April]: The Flower Moon](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/12aa6a_7c3e945d560a42299d136778a994ffa7~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_185,h_210,fp_0.50_0.50,lg_1,q_30,blur_30,enc_avif,quality_auto/12aa6a_7c3e945d560a42299d136778a994ffa7~mv2.webp)

![Kawoni [April]: The Flower Moon](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/12aa6a_7c3e945d560a42299d136778a994ffa7~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_74,h_84,fp_0.50_0.50,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/12aa6a_7c3e945d560a42299d136778a994ffa7~mv2.webp)

![Anvyi [March]: The Windy Moon](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/12aa6a_0119c7402f6f43038527f4d6c2f81970~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_183,h_210,fp_0.50_0.50,lg_1,q_30,blur_30,enc_avif,quality_auto/12aa6a_0119c7402f6f43038527f4d6c2f81970~mv2.webp)

![Anvyi [March]: The Windy Moon](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/12aa6a_0119c7402f6f43038527f4d6c2f81970~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_74,h_85,fp_0.50_0.50,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/12aa6a_0119c7402f6f43038527f4d6c2f81970~mv2.webp)

Comments